Seeing Blockchain Like a State

When I talk to crypto-native people, I hear the phrase “why does DC hate crypto” a lot. My friends don’t understand why “the government” is trying to stamp out their new innovation. Or, for those who think they do understand, their reasoning usually boils down to a libertarian accusation of corruption and regulatory capture which requires that old systems should be burned to the ground before new systems can flourish.

In contrast, from the DC perspective, I’m constantly talking to people skeptical that this new innovation will be the one to change it all. Longtime DC hands have seen hundreds of tech "revolutions" with very few delivering on what they promised. Remember when Bill Gates and other software engineers were promising the information superhighway, only for the internet to emerge? No? Well someone in DC - who bought that vision only to be burned - does!

DC and crypto are not inherently opposed to each other, but right now they’re speaking past each other. The government side asks for blockchain companies to comply with old regulations, and blockchain companies tell the government those regulations can’t apply or don't work. This cycle repeats itself over and over again, with both sides talking past each other and no win-win scenario even found.

I recently re-read James C. Scott’s “Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed,” which focuses on the basic desire of a government - to make the world legible. Scott’s book provides insight into how web3 builders can make it easier for governments to understand their products without compromising on their core values.

DC doesn't hate crypto, it just doesn't understand it - yet.

If you like this article, share with your friends, and subscribe by clicking below:

The Unnatural Natural

Systems of Order

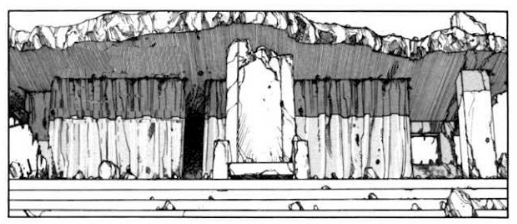

If you’ve ever flown across the country, you’ll recognize the familiar pattern of American farmland. Multicolored grids shaped by rivers and roads. However if you take a step back, this familiar pattern is actually totally unnatural. Hundreds of years ago, the farmland pictured above was likely natural plains land, no distinction in what plants were growing on plot 1534 vs. plot 8876. Instead of interrupting a perfect grid, the river above was likely the source of growth, with lots of plants near the river and trailing off further away.

When we look at the world, amidst the chaos, there are giant systems of order. We don't notice these systems because they seem natural to us. It’s natural that everyone have a first, middle, and last name. It’s natural for everyone to have a birth certificate. It’s natural to use small strips of green paper to pay for things instead of bartering with goods.

These “natural” systems of order are in fact very unnatural. A few hundred years ago, a first name was all that was needed, and last names were much more contextual - Johnson (son of John), Baker (occupation), Sutherland (area in Scotland). Today, on a planet of more than 8 billion people simply using a first and last name isn’t enough, and three names is struggling to uniquely identify each person as well! Perhaps in the future we’ll all need four names to properly identify us.

In Seeing Like a State, Scott argues these unnatural systems of order have been pushed forward by governments as they attempt to "see" the world.

The State and Legibility

Mapping the World

For all intents and purposes, the earliest governments were blind. They knew very little about their subjects, how much wealth they had, how much income they were making, their location, their identity, etc. To surmount this lack of sight, Scott argues that the state began to map its surroundings by standardizing measurements. This standardization allowed for easier comparison between categories and people by minimizing intangibles. If apples and oranges are too difficult to compare, the state would create a “fruit” category, abstracting away the specifics of the objects which can be measured and compared.

This shift towards measurement and order led to the creation of all kinds of systems which enable the government to “see.” This includes things like permanent last names (distinguishing Jack A from Jack B), the metric system for weighing objects, the standardization of letters and grammatical structures, and many more. In every case, government officials took complex, illegible practices and created a standard grid by which they could be recorded and monitored. In this way a ledger describing which person owns which plot of land is not just about organization - it is also about control. If Jack A owns plot 123, the state can force him to pay taxes on it, or punish Jack A through the use of force to take away plot 123. By giving its categories the force of law - follow the IRS rules or at some point men will come and force you to - the state creates systems that it can both understand and control.

By simplifying complex systems, governments are able to “see” them. In one famous example, Scott describes the advances of the German government in measuring, organizing, and standardizing of a forest in the 1800s.

Through careful observation, German foresters and mathematicians created an elaborate table of calculations related to trees organized by size, age, maturation, and growth rates. These charts were used to calculate the most efficient way to harvest and grow the trees to increase lumber yield. To facilitate increase lumber, German forestry science attempted to create a “perfect” forest. This meant creating a forest which was easier for experts to count, manipulate, measure, and assess. In the short-run, this uniform, easily measured forest was a great success. However, in the long run, the “perfect” forest ruined the soil, caused local wildlife to flee, and nearly destroyed the entire ecosystem.

Instead of examining the actual trees and health of the forest, planners were focused on the abstract tree - the tree in their charts. By simplifying and abstracting a complex system, the forest planners eliminated essential components of what made the forest healthy and sustainable. As the saying goes, “what gets measured gets done.”

This example sticks in my mind because it shows how the best intentions of the state, to increase lumber yields, nearly ruined an entire ecosystem. Governments can’t see individual trees, they can only see the abstract tree, how many nutrients it will need, and what volume of firewood could be expected. The state account for intangible components, it can only see if something checks the box or not. When new innovations come along, governments need to invent new boxes or adapt old boxes to "see" the innovation.

Blockchain illegibility

Draw clear parallels!

Today, blockchain and web3 apps are illegible to the US government and its bureaucrats. I often ask web3 creators if blockchain is a technological revolution or a financial revolution. Sometimes, they’ll say “it’s both!” This answer is exactly the challenge confronting web3.

New technical primitives will always lead to confrontation and challenges when they run up against old laws. For example, the red flag laws required that automobiles have a person walking in front of the vehicle waving a red flag to warn people of the approaching car and limiting the speed of the vehicle to the pace of a walking man.

However, it’s important for blockchain companies to make their technologies as legible as possible. For example, most tokens should have an explicit comparison to a technology of today. A lot of tokens today are in fact securities; but they’re also something more! NFTs can be both an investment, and a subscription to a digital country club. These “both” scenarios are too far of a leap for regulators. Financial regulators like SEC Chair Gensler see the financials aspects of crypto and say “hey that looks like an unregistered security!” Technology and cybersecurity regulators like FTC Chair Khan say “that looks like a consumer SaaS product!”

It’s important for new projects to be explicit about what they’re tokenizing. Is it a financial product? Does it have a claim on cash flows? Is it a collectible? Is it a piece of art? Is it a digital country club? etc. Clarity in this aspect will help not only blockchain projects but also government regulators. Blockchain projects with clear parallels will have clarity on what product features they’re building and why. At the same time, increased parallels will enable government actors to have more insight into which regulations should or shouldn’t apply.

Increased legibility will not only help clarify boundaries for regulators, but it will also help clarify lanes for legislators and the courts. For example, the more parallels a blockchain applications have to a non-financial use case, the less-likely such applications will be deemed a security or financial product. Regulators have limited resources, and famously only like to pursuit cases they believe they will win. As the saying goes, “bad facts make bad law,” meaning that regulators will pursuit slam-dunk cases and use the ruling as leverage over more difficult cases. In contrast, a company like SoRare, which draws very explicit parallels to baseball cards and card collecting, has not been in regulatory trouble (at least not that I know of at time of writing).

In response to this argument, some builders have responded that this runs counter to the regulatory game theory. Basically, if you parallel any current use case too much, you only make it easier for regulators to come after you. So, they reason, it’s better to triangulate between regulators and hope that none will come after you. Unfortunately, while this may have worked in 2015, I don't think this still holds true. Financial regulators like SEC Chair Gensler and CFTC Chair Behnam are suing just about anyone they can as they fight for regulatory jurisdiction over crypto. Financial regulators have been clear that they believe blockchain-based assets fit "box" they are tasked with watching. Unfortunately for crypto, the only parts of the government that believe they can "see" blockchain are financial regulators. This jurisdiction battle between the SEC and CFTC is good for no one, but is a result of the illegibility of many aspects of crypto.

Skeuomorphic Web3

Increased Legibility, Decreased Control

While I am calling for web3 to increase its legibility, I certainly don't want the government to gain centralized control over the blockchains and web3. History is littered with examples of governments using centralized power in awful ways, though I will point to the previous example of the German forest. The regulators didn't mean to create catastrophic consequences by organizing a forest - but they did! While outside the scope of this post, Seeing like a State outlines in excruciating detail the ways state control can lead to a prostrate society with no ability to resist.

A popular use case for a government controlled blockchain would be a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). China is rolling out one now, and the Biden Administration has tasked its agencies with studying the costs and benefits of implementing a CBDC in the U.S.. I am incredibly skeptical that a CBDC is a good idea. Instead, with a slight increase in legibility, web3 can serve as an empowering ecosystem for everyone. The decentralized nature of a blockchain makes it very difficult for government actors to control, even if they can “see” it.

Under Steve Jobs, Apple was famous for its skeuomorphic designs, or when a designer mimics old styles in a new environment. For example:

Note that the note app mimics a yellow legal pad, the Newsstand mimics a physical magazine stand, and the voice memo mimics a microphone recording. Today, now that consumer are more comfortable with digital interfaces, Apple has adopted a more minimalist design ethos:

Blockchain creators should think of legibility in a skeuomorphic way: on-chain products should be made more legible even if underlying blockchain logic is not. Both users and governments should be able to find parallels in blockchain products to products they already use. For example, create a token which is an on-chain security and a second token that is tokenized art - dont combine these into one, illegible token.

Blockchain creators should help states “see” blockchains by aligning their products with existing product categories. Substantially similar products, new ways of providing them. While some will complain this adds extra, unneeded complexity, what is the price-tag for being sued into bankruptcy by the SEC? This increased legibility will help bridge the gap between “DC” and crypto-native builders without giving up decentralization.

-Michael

If you made it this far, you'll probably like some of my other articles. Click below to make sure you don't miss one: