The Lean Startup

The Lean Startup was written by Eric Ries in 2011. In the decade since, startups have used it as a guide to systematically advance their business. According to Ries, the world is full of failed businesses which had the right idea at the right time. Instead of asking “can we build it” companies need to be asking “should we build it?” The business and marketing of a product must be considered as important as the engineering and product development. Ries argues successful startups can be engineered by following the correct process, which means successful entrepreneurship can be learned and taught.

The book is broken down into three sections: Vision, Steer, and Accelerate.

Section one of the Lean Startup focuses on defining a startup and what differentiates it from a traditional business.

According to Ries, the primary difference facing startups is the level of uncertainty. While traditional businesses face uncertainty, startups face extreme uncertainty. To evaluate trade-off decisions under extreme uncertainty, startups must use learn to quickly and accurately assess underlying assumptions of the business. The goal of a startup is to quickly determine a product customers want and are willing to pay for.

Startups and established businesses have two different goals: a startup is looking to create a product which solves a consumer’s problems whereas an established business is looking to iterate and improve their existing product.

Before creating a startup, entrepreneurs must ask themselves the following questions:

- Do consumers recognize the problem you’re trying to solve?

- If there was a solution, would they buy it?

- Would they buy it from us?

- Can we build a solution for that problem?

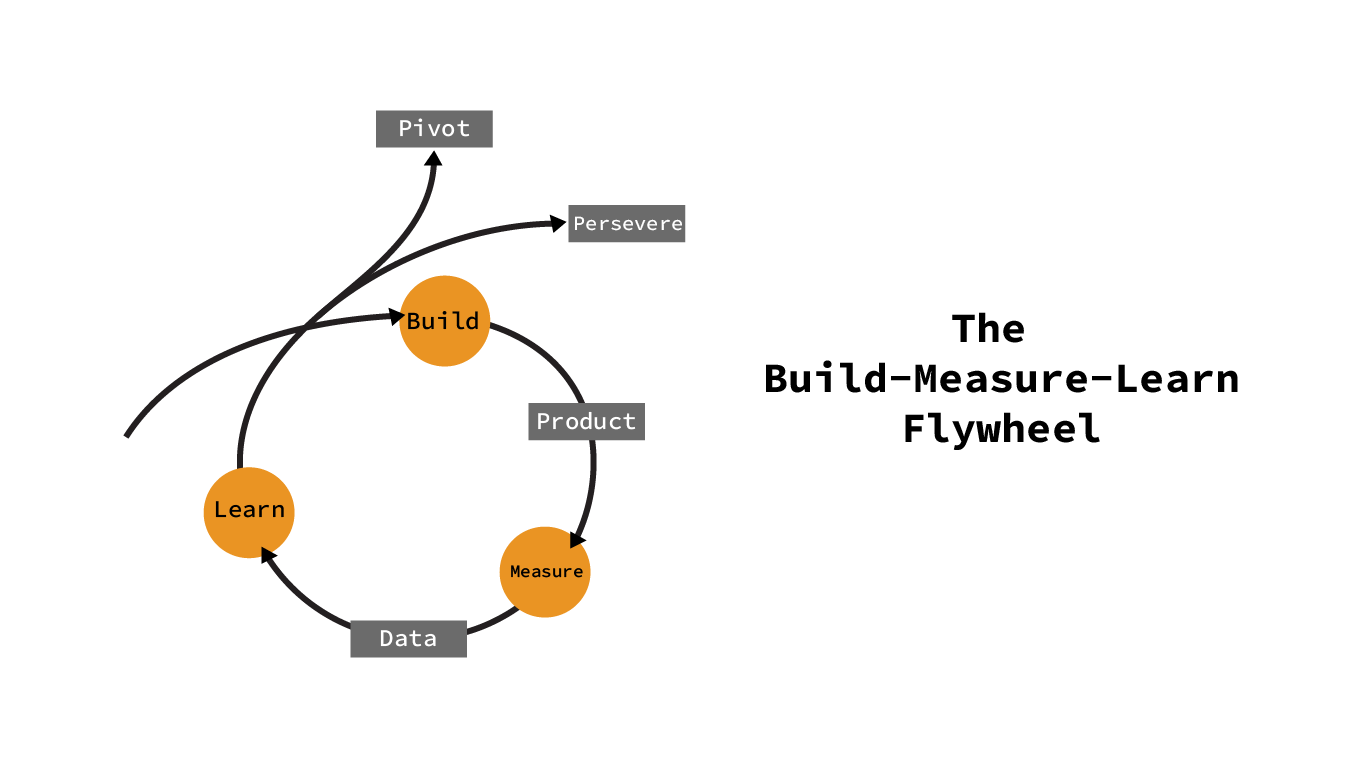

The middle section of The Lean Startup is the largest, providing a roadmap for entrepreneurs to follow when they begin to build a startup. The most important concept of this section, and arguably this book, is the “Build-Measure-Learn” flywheel.

Every business is built on assumptions. Examples include “the customer will desire this product,” “stores will allow us to sell our product,” or “customers will tell their friends about our product.” Above all others, each startup has two core assumptions:

- Value hypothesis – Our product provides value to a customer by solving a problem.

- Growth hypothesis – We can build a sustainable business by building and selling this product.

The primary goal of a startup is to test these assumptions as quickly as possible. To do this, entrepreneurs must build a minimal viable product, the most bare-bones version of the envisioned product which can successfully complete one cycle of the flywheel.

The three step process is:

- Use a minimal viable product to complete one cycle of the Build-Measure-Learn flywheel. Use data collected to evaluate the business’ assumptions about the market.

- Using the baseline data, fine-tune the product towards the ideal metrics

- Pivot or Persevere

One important concept is that of vanity versus actionable metrics. The core benefit of the Build-Measure-Learn flywheel is its testing of underlying assumptions. If the data generated by the flywheel doesn’t test the business assumptions, its unhelpful. Vanity metrics, such as total users, does not speak to the viability of the business, which would more accurately be measured by users sharing the product with their friends. Measure what matters, not what makes you feel good.

Determining if a business should pivot or persevere is one of the most difficult decisions for any startup. This is why collecting the right data is critical. Ries notes the sign of a productive pivot is that engine-tuning activities become more productive than before. He also notes that if a startup isn’t making significant movement on the drivers of its business model, it’s time to pivot. There is nothing worse than optimizing a process which shouldn’t exist. If the business is moving in the incorrect direction, optimizations will not yield significant results.

The Lean Startup heavily pushes “just in time manufacturing,” which Ries argues will allow companies to increase throughput and pivot more quickly when needed. Ries uses the example of a single piece flow, which demostrates it is faster to fold and stuff 1,000 letters individually than it is to fold 1,000 letters and then stuff 1,000 letters. This slowdown occurs because of the added time it takes to organize the letters. Instead of finalizing each piece, extra storage and organization is added. This small batch method allows for faster pivots, defect detection, and continuous deployment. This allows for fast experimentation and prototyping.

Another concept is “pull” versus “push” manufacturing. Push manufacturing is the traditional manufacturing model: produce 1,000 units, ship them to a retail facility or warehouse, the consumer then visits the retail facility and purchases the product. This method “pushes” the product ahead of demand, requiring complex forecasting of consumer demand. In contrast, “pull” manufacturing begins production of a product synchronously with consumer demand. Instead of producing batches of 1,000, the company produces batches of 1 and ships to immediately fulfill demand. This allows for a perfect allocation of resources, eliminating the possible of producing 1,000 units and only selling 800.

There are three engines of growth: sticky, viral, and paid. Sticky relies on high customer retention rate and a company expects that a consumer will continue to use the product once they start. Viral relies on spreading from person to person and carefully tracks the “viral coefficient,” or how many new consumers come from a user. Finally, paid relies on a recurring fee paid by the consumer. The paid engine of growth carefully tracks returns on acquisition cost – no company should spend $1,000 per customer if the product costs $900.

- Politicians vs. Innovators – One of the most interesting ideas from the Lean Startup comes from increasing the amount of ideas which are tested on customers. In Ries' framework, if an idea can be properly tested, it should be. In combination with the small batch and continuous deployment concepts, Lean Startups should constantly be experimenting with thousands of tweaks. In contrast, traditional businesses have much slower development cycles, sometimes only making on significant change per year. In this framework, thousands of ideas are competing to be the one idea which is implemented. By only implementing a small number of innovations employees are incentivized not to be good at creating innovative ideas, but to be good at the internal politics of implementing their idea over others. The shift from innovation to office politics is frustrating for all and limits the pace at which teams operate.

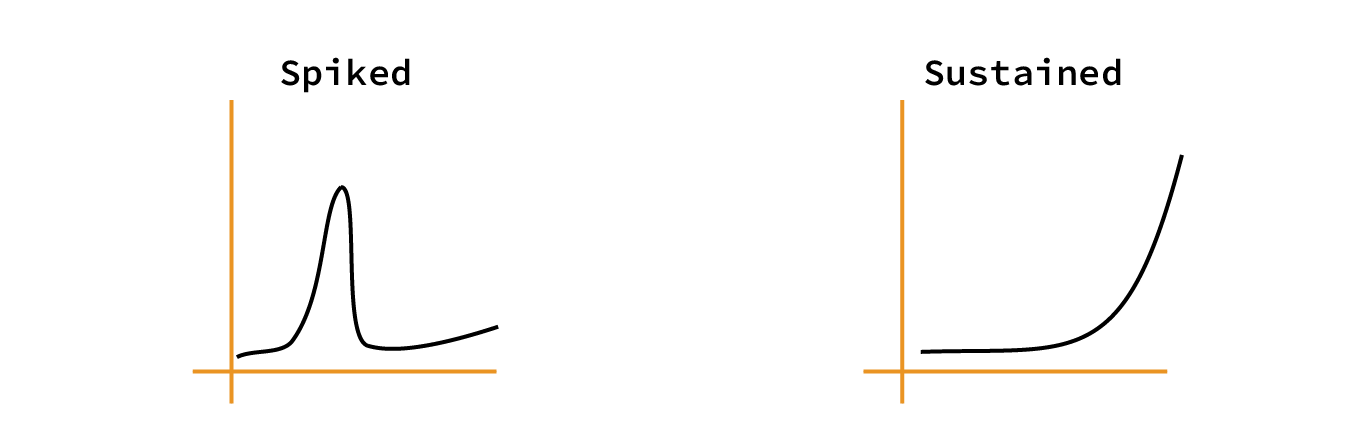

- Spiked vs. Sustainable Growth – By focusing on testing the underlying assumptions of a business (growth and value hypotheses) the Lean Startup discourages investing in areas outside of the core businesses. For example, while purchasing a Superbowl TV ad may spike the total users of a product. However, if the product is not solving a problem for the consumer, growth will not be maintained. Over-capitalized startups can burn cash to grow the business. However, without a truly functional growth and value hypotheses, the businesses will fail. I recently saw this tweet about TikTok spikes, which perfectly illustrates this point. Going viral is great, but without a well calculated value add, consumers will be on to the next big trend and value will quickly crash. The goal of any business is to build a sustainable value-add, not a viral one-hit wonder.

- Constant Innovation and Iteration – As discussed in my article on the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the world is moving towards a “____-as-a-service” model. Similarly, the Lean Startup discusses the movement towards continuous innovation and iteration. As markets change, businesses are pivoting and innovating constantly to maintain market share. Consumers are increasingly unlikely to accept decade-long iteration cycles. Businesses are no longer able to capitalize on innovations over a long period.

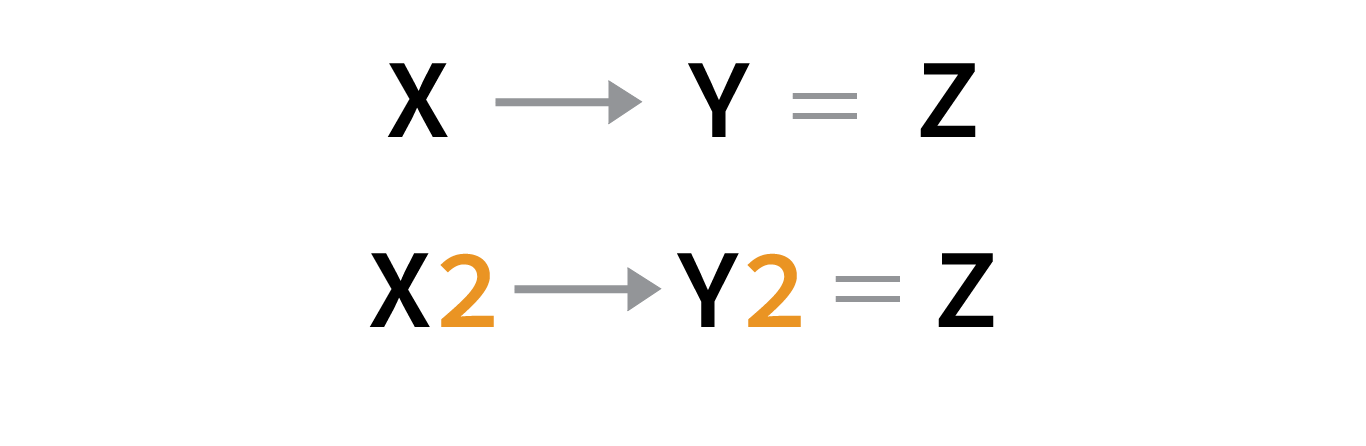

- Leaps of Faith – Some baseline assumptions about the state of the market are untestable prior to launch. The Lean Startup calls these “leaps of faith.” Most leaps of faith are formatted by analogy: Previous technology X was used to win market Y because of attribute Z. We have a new technology X2 that will enable us to win market Y2 because we too have attribute Z. I think this comparison framework is an excellent way to quickly sell a story with depth across various industries. The following is an industry standard for political candidates: “Candidate X won market Y because of attribute Z. I (Candidate X2) will win market Y2 because I also have attribute Z.” This formulation allows difficult to test axioms to be compared and contrasted with others.